Object Domicile

Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South AfricanObject Origin

None NoneThis object was donated by the artist, Dumile Feni, to the South African National Gallery in 1968 after representing South Africa in the Sao Paulo Biennale.

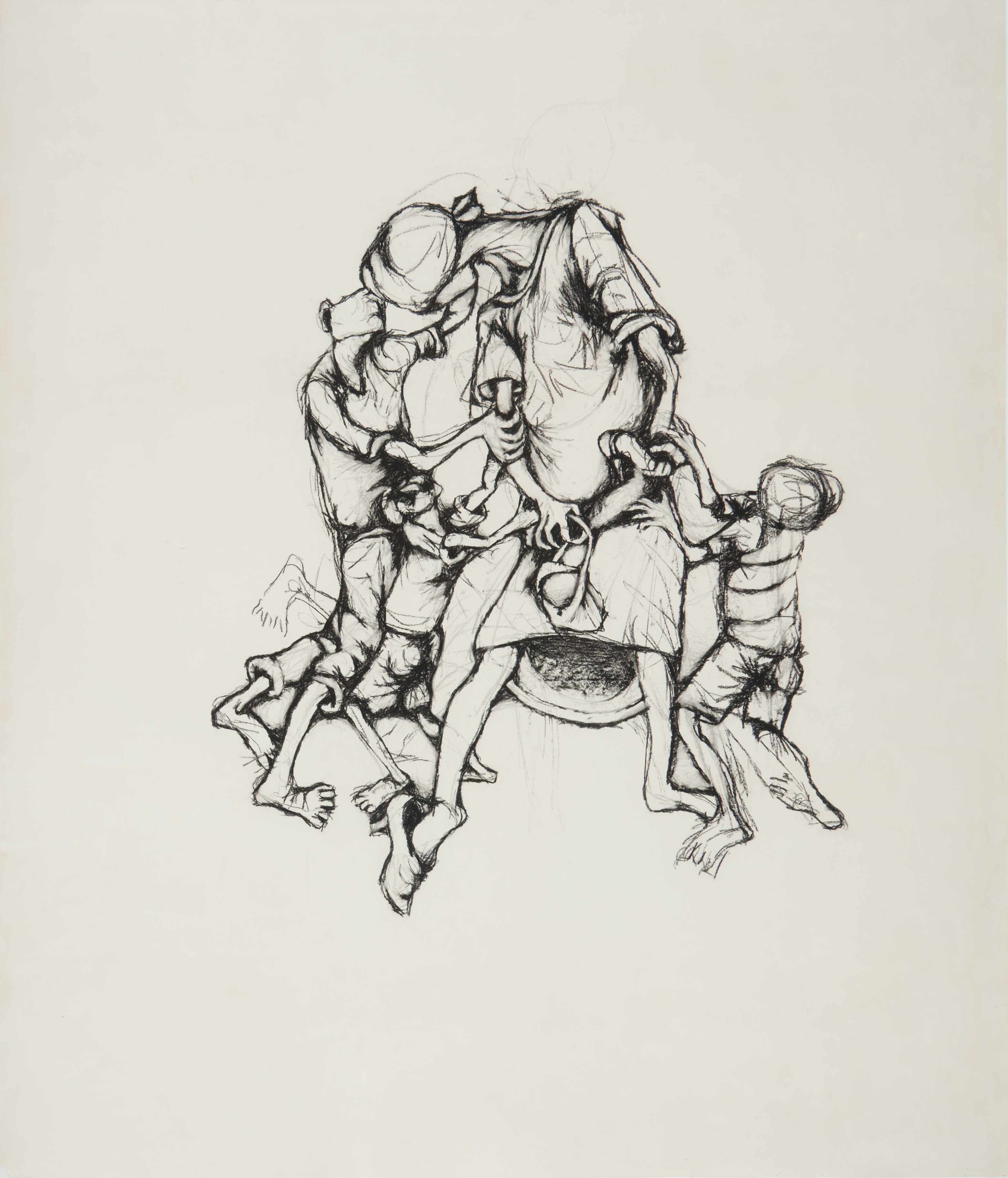

'A group of children' is said to have been the first artwork by a black artist to make it to the archives of the South African National Gallery (iSANG). Dumile Feni, the artist, donated it himself, at the time when he was clouded by the controversy of having represented the South Africa's apartheid government as a participant at the Sao Paulo Biennial the year before.

Gathered around a motherly figure, the title of the artwork still seemed odd for the drawing, despite its acknowledged “group of children.” Omitted it seemed, was the woman whose presence seemed to bring together the children, as well as the compositional balance of the drawing.

At the time of researching the artwork, the South African National Art Gallery seemed to have very little information recorded on the art work. The drawing itself did not offer much in the way of its historical record and authenticity. This was not merely an impression; the drawing was neither dated nor signed. It being here seems to convey a very disturbing silence. However, this silence of the mother figure is held tight in each arm with no chance of escape. She shows no signs of struggle but embrace. She towers over the children both giving structure and balance in the framing of the work.

From the young ones, there is an aura of desperate excitement often visible when those who profess and promise spiritual enlightenment and wealth to the poor emerge. She is clutching at what seems like a purse. She could just be arriving from the place that steals parents from their children – work. Starring up to her are invisible faces in demand of affection. Her face is against us as she attends to her embrace. These invisible faces are made up and defined by skid marks of charcoal indiscriminately travelling from head to toe, and tearing through to flesh and fabric. Tearing and mending, the rough and the defined lines of life giving movements to the life in rags and bare feet.

She seemed essential in the making of the work. Despite her presence, her position as an object of focus, both for us the audience and the children who cling to her, according to the title, she is absent. She is an absence. The kids cling at nothingness. Will we ever know her?

‘Groups of children’`

How do we make meaning from obscurity? In the presence of the non-existent?

In this drawing, we see a woman held tight on each arm, with no chance of escape. She shows no signs of struggle, however. She towers over the children, giving structure and balance to the framing of the work. From the young ones, there is the aura of desperate excitement, often visible upon the emergence of those who profess and promise spiritual enlightenment and wealth to the poor. She is clutching at what seems like a purse. She could be just arriving from work, the pursuit that steals parents from their children. Staring up at her, invisible faces demand affection. Her own face is turned away from us as she attends to her embrace. The invisible faces are made up and defined by skidding marks of charcoal that travel indiscriminately from head to toe, and tear through to flesh and fabric. Tearing and mending, the rough and the defined lines of life give movement to the life in rags and bare feet. She seems essential to the making of the work. Despite her presence, her position as an object of focus for both the audience and the children who cling to her, according to the title she is absent. She is an absence. The children cling at nothingness. Will we ever know her? Her essence?

We can try and make of her non-being-there, of her nonontologicality, in ways coordinated by the simultaneously humanising and dehumanising notion of Ubuntu.

I encountered a thread on Facebook, where a friend of mine, Rithuli Orleyn, shared the following post by Stanley Sello: ‘I’m quite fascinated by how ants can create a complex social structure for themselves without a single committee meeting.’ Stanley continued, ‘Maybe they know something about Ubuntu…’. This is an interesting assumption, especially if you think about it within the confines and structures that form and govern our world, where ideological alliances distinguish insiders from outsiders. A comment from Kabelo Prince Maduno disputes not the initial lack of committee structure in the statement, but the seemingly inherent attribute assumed to be a guiding source of their harmonious organisation. He comments, ‘I doubt it’s Ubuntu, it must be ubuAnt … this is a higher consciousness, our problem started with the gift of language. Minutes later, on the shared status, a friend of his comments, ‘How do we know that they don’t have committees?’ Despite the original post’s intention to give the ants some sort of mystical attributes, and of course with no ill intent, there is now a requirement to base such assumptive logic on concrete evidence. As if an obligation to our symbolic world, Orleyn responds, playfully at first, that ‘Wellerrr, we are yet to see their committee meeting minutes, perhaps?’ One can see a trigger in his thinking, a reminder of a recent attribute governing our symbolic world, a comment made by a Democratic Alliance leader, Hellen Zille, so he comments further:

Remember when Hellen Zille also said about us, we had no justice system and no piped water system, well … she probably was looking for designated magistrates & judges, written legal code, the entire value-chain that links jurisprudence to correctional facilities. We had none of those signifiers. We had different signs & symbols for justice, harmony, balance, righteousness, peace, and healthy social fabric. We had neither stenographer, nor the word stranger in our language. ‘Correct,’ ‘well’ or ‘wellness’, righteousness, and ‘justice’ shared the same word ‘lunga’ (do right), a word that also means ‘holding the line’ (like ants), a word that means ‘upright’. We clearly clubbed too many things that your Zille types could only recognize in their pigeonholed formats: wellness: medicine (health & psychic health), justice (law, philosophy, politics), righteousness (religion, spirituality), hold the line (belief, ideology), upright (paleontology, biology), correct (attribute or instance of actionable consciousness, reflexivity & self-critique). So maybe like Zille we are wrong to look for committee meeting minutes. But if we are right about anything, that something is likely this: the system of ants’ sociality resembles and resonates with key tenets of Ubuntu bethu…”

Intent on critiquing Zille’s obviously anti-Black position on how the same institutions formed in the mould of colonialism and Whiteness – structures whose function has been (as it still is) to keep intact this mould – are a symbol of progress, poses a threat of an exaggerated precolonial African utopia. In speaking to what was in the pre-colonial, Professor George Ayittey reads forms of restorative justice held through a consensus formed by different village centers that the Ashantis called ‘asetena kese’, the Igbo call ‘ama-ala’, the Somalis ‘guurti’, the Shona ‘dare’, isiZulu ‘ndaba’ and Setswana ‘kgotla’, to name a few. The above-mentioned point less as evidence of the existence of a prison system, which in itself does not disqualify a justice system – in particular when preventative measures (which took priority) fail. Here we find ‘fine’ at least and ‘banishment’ at worst, all under a committee of community leaders. However, like the woman surrounded by children, while some of these structures exist, they exist as silence in the larger system that coordinates our sociality.

Dumile Feni’s drawing ‘Groups of children’ has a special place as a historical piece in the Iziko South African National Gallery’s (ISANG) collection. It is said to have been the first ever artwork by a Black artist to be collected by ISANG, at a time when the gallery was accused of having no artworks by Black artists. The work was donated by the artist himself, a year after he controversially took part in the 1968 Sao Paulo Biennale, and was accused of representing the apartheid government. Despite being collected after the era of colonial plunder, not much information exists about this work. Precolonial objects’ lack of documentation in museums today is often ascribed to an assumed precolonial Africa said to have been more ‘communal’ than ‘individualistic’ pre-colonising Europe.

This essay is not an attempt to revisit and correct historical inaccuracies, and neither is it an attempt to portray Africa as a nostalgic, historical utopia. The chronology of history itself – prehistory, history and posthistory – writes Olu Oguibe (1999), ‘… is evidence of the arrogance of Occidental culture and discourse that even the concept of history should be turned into a colony whose borders, validities, structures and configurations, even life tenure, are solely and entirely decided by the West’. Oguibe elaborates on how this narrative is a basis for the West’s self-erasure of pre-modernism and the rest’s replacement with primitivism in the triad that is premodernism, modernism and postmodernism. Such atrophy, absence and/or the incompleteness of the narrative opens up a space, a ‘gradual re-invention … and the always available African worthy of the Outside Gaze’ (Oguibe, 1999).

We visited ISANG on the morning of 31 July 2018, as part of the Centre for Curating the Archive’s Honours in Curatorship course, for a session titled: ‘Defining and recording relationships between museum collection objects’. As the class gathered around a glass-encased wooden carving with neither date nor maker acknowledged, it provoked a conversation about its historical ambiguity and how African objects were obtained during colonial times. One argument in defense of the maker being unacknowledged was that it might have been attributed to a collective or community, rather than an individual maker. While this carving’s attribution to the community was seen as an essence of pre-colonial Africa, Feni’s drawing, despite being attributed to its maker, still lacks thorough documentation. This is synonymous with what Oguibe calls the ‘imposition of anonymity of the native’, where one’s production is relegated to the zone of culture as a presupposition of primitivism, or when one is called upon to narrate the self, ‘novel strategies are employed to anonymize by disconnecting the art from the artist … focused on detailed biography and on the peculiarity of the work’ (Oguibe, 1999). The distortions of historical inventions that construct Africa persist, but it is what Oguibe has identified as ‘the effaced African artist, the faceless, anonymous native, the tolerable, consumable Other who, stripped of authority … is opened to the penetrative and dominatory advances of the West’ that he sees as a pornographic trope.

The appeal of the faceless, anonymous native is in the fact that she is also a pornographic object, a docile, manipulatable object of desire and pleasure. Pornography as a strategy rests on the localization of desire and the intensification of pleasure through the effacement of the subject, the detachment of the locality of desire from the web of subjective associations and reality that impinge on the possessor’s sense of social responsibility. In other words, its principal device is the objectivisation of the source of pleasure. For maximum derivative effect, the purveyor as well as the consumer of pornography must detach and frame the object, enhanced through the combined mechanisms of magnification and erasure, filling the frame with only that which satisfies the specifications of desire. Even this is further aided by positioning the object within appropriate narrative, the right sound, the further from speech the better, all of which, by playing on the extremes of perversion and provocativeness, sufficiently hold it within the frames of the spread. Of course, the erasure of the subject, or her transfiguration into the realm of the fantastic, consolidates the purveyor’s fiction of ownership, and thus power. And power, the ability to possess unquestionably, to exercise uncontested authority and manipulate at will, is the essence of pornography. (Oguibe, 1999: 23)

Works by Black artists are seen to have moved from the communal or tribal to the individual. There is an implication here of a sort of progress of the individual artist that does not necessarily change how Black artists’ work is treated post-colonially, but how Black artists themselves have been written historically into adopting an outside-the-tribe, grown-up attitude that shifts to the ‘exceptional’, first-Black phenomenon – a pat on the back. As a mark of certitude, the artwork misses that one element that makes the work individual, that which seems to authenticate the ‘real’ of an artwork – the signature. It is fascinating that a work donated in the late sixtie,s and whose maker passed on in 1991, could not have been signed in the intervening decades. The work must have been gathering dust somewhere in the darkness of the museum’s storage facilities, and only after his death was its existence ‘acknowledged’. One cannot escape the recrudescent erasure at the heart of this acknowledgement.

On 24 September 2018, I arrived late for a brief cultural day session at Iziko South African Museum, having mistaken ISAM for ISANG. My classmates were already engaging the audience, and were positioned next to the easels that supported their objects. My first glimpse of the object on my easel made me uneasy because of the unfamiliarity of the drawing’s composition. I dropped my bag and took my position next to the drawing. Still a Feni, the drawing was foreign to me – the woman was not in the drawing at all. ISANG had given me the wrong artwork.

Unlike Christopher Wallace’s lament, ‘You’re nobody (til somebody kills you)’, we can easily say now ‘You’re nobody even in death’. The absence of being that is at the heart of such anti-Blackness comes back as the objectification of Feni the illiterate, who had not gone beyond the ‘primitive’ communication of symbols, never mind thought. As if we never left, we are back to obscurity, opened to analysis and constant rediscovery. As a consistent historical manufacture, the gaze never left. The community transforms and comes back in the form of ‘Ubuntu’. Our container, devoid of humanity in the modern sense, only contains ‘peace’, ‘tolerance’ – in the form of ‘anti-Blackness’ and injustice. ‘Ubuntu’, the inherent harmonious essence guiding our current situation, has been a rallying point in the argument for peace that must be upheld in anti-Blackness. The essence here is a troubling phenomenon. Though it is not explicitly and concretely attributed to the being of Blackness, it assumes an attribution that comes as a constant reminder. If we contextualise this form of objectification within Slavoj Zizek’s Lacanian reading, in his Object and Ontology Duel/Duet with Graham Harman, of how the real of the object is never truly impenetrable, we have to look at Whiteness as a subject whose ‘object-hood is unavailable to itself’. In its radical failure or denial to know its object-hood, it therefore needs a paradoxical object of desire, which in this instance becomes Blackness – which must constantly seek validation that can never be.

Here we see White anxieties play out. This is, as Zizek points out, the subject/object relationship, a ‘horizon with no beyond’. Here, the real of the work deliberately becomes the object of the never full penetration. In the period from the time of Feni’s donation to the time of his death, all necessary technical and conceptual information could have been collected and accurately documented. Such a deliberate failure does not seek rectification, for it reveals something to us; this lack of information is not a betrayal of the real of the work. We should read from it its true reveal that is the distortion of the real. This failure or denial to accurately represent the work and, therefore, the artist, offers us a truth about social reality, and so this erasure or falsification, as Zizek posits, ‘registers our real social antagonism’.

The notion of essence is not to be shoved under the carpet, nor is it to be discarded, but contextualising from the above assertion, from what the real reveals. Harman’s conversation with Zizek is again instructive here, as he remarks on the notion of the Jew’s essence that:

If somebody says Jews conspire and manipulate, that’s not quite anti-Semitism yet. Anti-Semitism is the next step, where you say ‘they conspire and manipulate because they are Jews’. In other words, there’s some hidden essential core that causes the conspiracies and manipulations.

Harman reads this argument as ‘Jewishness is some real entity outside the individual cases’, as an argument against generalisation and posits that ‘You can never know what that essence is.’ He argues that the problem with essentialism is not that it does not exist, but is when there are claims to know it. And this, he claims, takes away the real of the object.

Further Reading

Oguibe, Olu. 1999a. Art, Identities, Boundaries: Postmodernism and Contemporary African Art. In Olu Oguibe and Okwui Enwezor (eds). Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Market Place. London: Institute of International Visual Arts .

Oguibe, Olu. 1999b. In the Heart of Darkness. In Olu Oguibe and Okwui Enwezor (eds). Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Market Place. London: Institute of International Visual Arts.

Slavoj Zizek and Graham Harman in Conversation. YouTube video. Posted by SCI-Arc Media Archive on 12 September 2017. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdGeJWJsxto.